Paper vs. Screens:

What’s the Best Way to Teach Kids to Read?

By Raquel Reenders, First Grade Teacher

Providence Classical School uses a “low-tech” model compared to today’s public schools. In the Grammar and Logic stages (PreK-8th grade), students do not use tablets or computer stations in the classrooms. Instead of making digital presentations, young students use “old school” posterboards, models, notecards, and costumes. Are Providence Classical School students in danger of falling behind in our modern world?

The modern way of thinking touts that children need to learn computer literacy, so technology needs to be introduced in the classroom from a very early age. In his book The Tech-Wise Family: Everyday Steps for Putting Technology in Its Proper Place, Andy Crouch states that the idea that young children need to become computer literate is misguided. He claims that reliance upon technology in primary education is problematic because it makes things too easy. Low-demand, passive activities may be fine for leisure, but they do not help us learn. We need to be challenged and encounter difficulty in order to learn and grow. We learn best when we learn according to who we are: human beings — body and soul together. When our muscles, senses, and minds act together, we learn!

God also designed us to live in community. We learn better when we learn together. Our goal at Providence is not just to teach facts and skills, but also to exemplify how to be the image-bearers God created us to be. This includes training students how to relate to one another. We know that we are partnering with parents to help shape their children to that end — cultivating godly wisdom and virtue and a love for God and each other.

We believe that teaching children to read using physical, paper books helps form character traits that align with our school’s mission and vision.

Why is excellent, intelligent reading important?

Education is formation. As Sarah Mackenzie says in The Read-Aloud Family: Making Meaningful and Lasting Connections with Your Kids, reading is key to the formation of our children because it “inspires heroic virtue,” “nurtures empathy and compassion,” and “prepares for academic success.” Well-formed readers look like the portrait of Providence Classical School graduates who are known for their character, knowledge, discernment, and communication.

- Character

We desire students to walk in godly character. Books help students “to practice living through an experience vicariously” and to “practice living with virtue, and failing at virtue” in their imaginations says Sarah Mackenzie. Reading stories is a training ground for life. - Knowledge

We want students to have enough background knowledge and vocabulary to begin to understand what they are reading and, at the same time, gain more knowledge and vocabulary for them to bring to the next book and conversation. Reading also helps students make connections between various subjects, to ask questions, and to think. - Discernment

We want children to develop discernment by exposing them to a curated collection of texts that will help them recognize what is true, good, and beautiful. Furthermore, we want them to develop a taste for truth, goodness, and beauty, especially as expressions of God’s character, so that the counterfeits the world has to offer will not satisfy them. - Communication

Books also help students to learn to communicate. At the heart of communication is community. When students read books, they connect to the characters and learn to view others as made in the image of God. Books also help them learn to listen and empathize with other people. When we learn to listen before we speak, we communicate in a godly way.

How do children learn to read?

Well-formed reading is the goal, but how do you get there? For beginning readers, it starts with building a neural network in their brains. They must connect the part of the brain that recognizes shapes and faces to the part of the brain that processes sounds and to the motor part of the brain that helps articulate sounds. These must also connect to the part of the brain that processes meaning and to the area that handles language syntax because groups of words and the order of words change the meaning of sentences. Young readers must also form a connection to the emotional part of the brain. The brain of a child who learns to read changes physically as new gray and white matter are formed.

In my job as a first grade teacher, I have a front-row seat to watch children learn to read. Children need a lot of repetition and effort to connect letters to sounds, sounds to words, words to mental images and meanings, and more. It is an exciting time for them as the world of words begins to reveal its secrets. I cannot see into their brains, but I know they are building a complex neural network — the reading brain.

For those of us who have already become skilled readers, the neural network is so strong that we cannot help but read what we see. The reading process is almost instantaneous. Furthermore, we can think about what we are reading while we read it. We can immerse ourselves in the reading experience. It is nothing short of amazing and a reminder that we are fearfully and wonderfully made!

Does the reading format make a difference?

We have access to so much to read today. But are all reading experiences created equal? Is digital technology an aid to reading or an impediment?

A recent study found that we comprehend more when we read on paper than on a digital device, and this is true for both adults and children. I recently read an essay from a college professor lamenting that, in his 15 years of teaching, the reading ability and stamina of his students have declined. I hate to admit it, but I observe the same change in myself. Reading is more work than it used to be. I find it harder to get into a book than I did before. I find it harder to concentrate and stay focused. I do not read for as long as I did before. What is happening to me? Am I the only one?

My smartphone is making me dumb, and I am not alone. Research shows that adult attention spans are shrinking. Memory is declining. And the elephant in the room is the smartphone. One study shows that having our smartphones near us negatively affects our cognitive performance even if they are silenced or turned off. People whose phones were in another room outperformed those who had their phones nearby.

Why is reading comprehension worse online/digitally than when we read printed material?

According to Maryanne Wolf, author of Reader, Come Home: The Reading Brain in a Digital World, when most of us read online, we use a “word-spotting, skimming” pattern of reading that follows a capital F or Z pattern. Reading online requires task switching, and we come primed for a distracted reading experience — click on a link, scroll past an ad, close a pop-up, or open a new tab in your browser. In contrast, when we read printed material, we slow down, read more deeply, and our comprehension improves.

If you spend the bulk of your time reading digitally, the rapid, scanning, non-reflective reading style can bleed over into your print-reading brain and cause difficulty with attention and comprehension. It may take some time, effort, and intention to reclaim your “deep reading brain,” but you can do it because you had a “deep reading brain” in the first place. You have what Wolf calls a “bi-literate brain” that can successfully switch between both types of reading.

Why does Providence prefer physical books over tablets and Chromebooks?

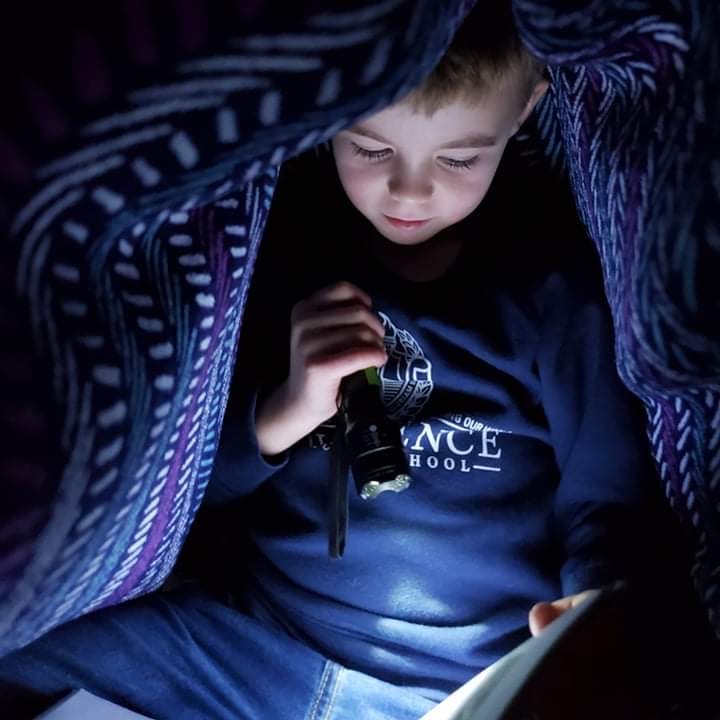

At Providence, we want to ensure children develop a thoughtful, reflective, deep-reading system. This necessitates learning to read with a “regular” book. If students go straight to technology-based reading, they are in danger of never developing this habit of deep reading because digital devices build a certain kind of reading habit — fast, shallow, and passive. Physical books build a different kind of reading habit — deep, reflective, and engaged.

For most children, digital reading comes with a preformed habit because they started using screens before they could read. Digital devices and their content are designed to be highly stimulating and entertaining but also passive. Screens create a taste for entertainment, a habit of inattention, a craving for novelty, a state of hyperstimulation, and a sense of urgency and speed. When children use screens to learn to read, they come with a built-in mindset about what the experience should be like. A developing reader is more apt to become distracted and crave diversion on a digital device.

Learning to read is hard work requiring focus, attention, and memory. It demands a lot of the reader but is also rewarding. A book does not passively entertain you. In a way, you become the battery power and software for bringing the book to life. The words take flight in your mind.

Besides encouraging the habits of attention, reflection, and imagination, here are some other benefits to reading a physical book:

- Books are physical and connect to our senses in a way that digital media cannot.

Books have a smell. You can hear pages turning, and you must slow down to turn them. You can feel how far along you are in a book by the number of pages to the left and right. Visually, there are eight corners to help us orient what we are reading with a physical place in the book. Scrolling erases that sense of spatial orientation, and e-readers have four less corners than a book and no physical feel for how far you are into the book. Studies have shown that we remember the sequence of events better when we read physical books, perhaps, because we are connecting it with a physical space in the book. - Books have a single purpose.

There is one thing to do with a book — read it. By contrast, digital devices are multitasking devices. We do not actually do two or more tasks at the same time. Instead, we rapidly switch our attention between tasks, and none of them receives our undivided attention. When we read on a device that has multi-tasking abilities, we must continually choose to stay on task. Choice overload is stressful and leads to a nagging sense that we are missing out on something. Stress does not improve comprehension. Even if you close every tab on your browser, distraction is just one click away. - Books do not require batteries or chargers.

No matter how long your book is unplugged, it will always be ready for you. You will not need to attach yourself to an outlet to use it. You will not need a password. It will never “die” right before the end. (Imagine the problems that inevitably arise in a classroom full of digital devices.) - Books are shareable.

The physical act of giving a book to someone is different than sharing a link. When you loan someone a book, you are giving them something to steward. You are hoping it will stir the same feelings in them as it did in you. If you give a book to someone, you are giving them a treasure. You want to share more than a book; you want to share ideas and conversations. When you are reading together, either parent and child or in class, you are forming a bond of community through your communication because you are literally “on the same page.”

At Providence Classical School, we celebrate reading with embodied experiences. Students get cozy with pillows and blankets to take a reading vacation. They taste green eggs and ham. They act out Aesop’s Fables. They dress up like book characters. They make boxcars. They perform a Shakespeare play. They host a book party. Through books we connect with each other and with people from different times and places.

So back to our original question: Are Providence Classical School students in danger of falling behind in our modern world because they learn to read the “low-tech” way? Not at all! In fact, PCS students are more prepared to face the challenges of life ahead because they have tasted the best experiences reading has to offer. They learn to love reading and, in turn, love learning. And an adult who enjoys learning is an adult who is thoroughly equipped for the future!

For more information on how Providence Classical School can develop a love of reading in your child, watch our video and schedule a tour today!

About Raquel Reenders:

Raquel earned her BA in biblical studies with a minor in linguistics from Calvin College. After college, she worked in the offices of a Del Monte Foods plant. However, God had plans for her to teach, and she was asked to teach 5th and 8th grade classes at a Christian school and to assist students who needed extra help. Raquel says she learned the most about teaching during her time as a stay-at-home mom for 12 years. When her youngest son entered first grade in 2014, she joined the Providence faculty as a Pre-K teacher’s aide. She is now in her eighth year teaching first grade. Raquel and her husband, Mike, have been married for 26 years and have three sons who are all part of the Providence family — David (Class of 2021), Philip (11th grade), and Mark (9th grade).

Sources:

Creamer, Ella. “Reading Print Improves Comprehension Far More than Looking at Digital Text, Say Researchers.” The Guardian, 15 Dec. 2023, www.theguardian.com/books/2023/dec/15/reading-print-improves-comprehension-far-more-than-looking-at-digital-text-say-researchers.

Crouch, Andy. The Tech-Wise Family : Everyday Steps for Putting Technology in Its Proper Place. Grand Rapids, Baker Books, 2017.

Kotsko, Adam. “The Loss of Things I Took for Granted.” Slate, 11 Feb. 2024, slate.com/human-interest/2024/02/literacy-crisis-reading-comprehension-college.html

Mackenzie, Sarah. The Read-Aloud Family. Zondervan, 27 Mar. 2018.

Staff, Kappan. “Maryanne Wolf: Balance Technology and Deep Reading to Create Biliterate Children.” Kappan Online, 1 Nov. 2014, kappanonline.org/maryanne-wolf-balance-technology-deep-reading-create-biliterate-children-richardson.

Ward, Adrian, et al. “Brain Drain: The Mere Presence of One’s Own Smartphone Reduces Available Cognitive Capacity.” Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, vol. 2, no. 2, Apr. 2017, www.hendrix.edu/uploadedFiles/Academics/Faculty_Resources/Teaching_and_Learning/Presence-Smartphone-reduces-cognitive-capacity.pdf, https://doi.org/10.1086/691462.

Wolf, Maryanne, and C J Stoodley. Reader, Come Home: The Reading Brain in a Digital World. New York, Harper, 2019.

Header image by Jorm Sangsorn on iStock.